‘How can a West Texas boy go to L.A.?’ Lincoln Riley’s journey from Muleshoe to USC

MULESHOE, Texas —

Ryan Kartje (LA Times) — Deep on the dusty plains of West Texas, where grain silos line the sparse landscape and a dry breeze blows loose tufts of cotton across U.S. Route 84, a stretch of railroad runs along a lonely highway. The Pecos and Northern Texas Railway companies laid the track here in 1913, cutting through this swath of Bailey County ranchland to connect the growing town of Lubbock to the border of New Mexico. A farming community sprouted alongside the track soon after — some 70 miles northwest of Lubbock and 30 miles east of the border — taking its name from the nearby ranch where, legend has it, the original owner found a stray muleshoe lying in the soil.

The rapid rise of Lincoln Riley, from small-town quarterback to one of the most promising football minds in America, is rooted deep in this arid soil. Ask anyone in Muleshoe about Lincoln, whose first name is enough around these parts, and they swell with pride. Lincoln, they’ll tell you, could’ve been anything. A rocket scientist. A doctor. Maybe even an astronaut. But he chose football, and his immediate success — with three College Football Playoff semifinal appearances in his first three years as head coach at Oklahoma — has become an inextricable part of the town’s story, one they’re more than happy to share, even if most can’t quite reckon with the latest twist.

Here in Muleshoe, the stunning news of Riley’s sudden departure to USC late last month was greeted mostly with sideways glances. Few believed it at first. California? Really? Oklahoma might’ve tested their allegiances as Texans, but Norman was still the Great Plains. Los Angeles, on the other hand … that felt like a world apart from Muleshoe.

“How can a West Texas boy go to L.A.?” asked David Wood, who coached Riley at Muleshoe High.

“It’s going to be a total change for Muleshoe to think about Lincoln being in California. That’s a whole ‘nother world than what he grew up in,” said Alice Liles, who taught Riley’s advanced English class and authored a book on the town.

Take a stroll along Main Street in Muleshoe; pay your respects to Old Pete, the mule monument standing guard near Muleshoe’s only stoplight; hit the livestock auction just outside of town; and maybe stop for a tamale or two during the lunch rush at Leal’s, the town’s beloved gathering spot, and you’ll start to understand what they mean. It’s hard to imagine a place any further away from Los Angeles. The only passing reference to L.A. found here comes from a novelty Rodeo Drive sign behind the bar at Rodeo, Muleshoe’s lone watering hole. Alcohol sales were first allowed in the town just three years earlier and to this day some respected folks still remain wary of setting foot inside the bar.

But everyone here trusts Lincoln. He was brought up in Muleshoe after all, raised with its good Christian values. Even his childhood mischief has become a part of the town mythos.

So when they hear insults hurled his way from Oklahoma, where the pettiness extended this week all the way to the state Senate, they spring quickly to his defense.

“My daddy would roll over in his grave if I said I was gonna root for USC,” Sam Whalin, the school’s retired maintenance director, says with a laugh. “But I think it’s a wonderful move.”

A statue of Old Pete stands near Muleshoe’s only stoplight and celebrates the role of the mule in Texas history. (Ryan Kartje / LAT)

Kyle Atwood, a close friend and Riley’s leading receiver in high school, expects USC flags to be flying in town soon enough.

“Lincoln knows exactly what the heck he’s doing. Going [to USC], he’s obviously ready for that challenge. He’s ready to be a part of that city and what comes with it. And Muleshoe, it’s a town that backs people from the community. There’s an intense sense of pride. Muleshoe always supports their own.”

The town is quiet on a recent Saturday afternoon as Colt Ellis, Muleshoe’s 31-year-old mayor, locks up at the family funeral home and leads an out-of-town visitor on a tour in his pick-up truck. The hustle and bustle is happening at the livestock auction down the highway, where sheep and hogs and goats are being sold at a breakneck pace. But the rest of Muleshoe moves at a crawl.

Family roots run generations deep in Muleshoe, making it sometimes feel like time is standing still. Ellis is the third generation to run the funeral home, which his grandfather opened in 1959. Theirs is one of many businesses in town that have been passed down, then passed down again, lending Muleshoe an ingrained sense of continuity and pride. Growing up here, Ellis says, it often felt like you were insulated from the ails of the outside world.

While other small Texas towns have faded off the map, the dairy business has kept Muleshoe’s population hovering steadily around 5,000. Most folks here seem just fine with that. As the young mayor explains, change often comes to town at a particularly cautious pace. No new houses, he says, have been built in 15 years.

Ellis is hoping to change that with plans for a new development on the edge of town, a project he hopes might convince folks fleeing Lubbock, 70 miles to the southeast, to take refuge in small-town living. He has other big ideas to move Muleshoe forward. But Ellis knows patience is an important part of his job description.

The Riley family came before most other fixtures in Muleshoe, settling in town in the 1930’s, not long after the town was incorporated. Both sides of the family were rooted in the farming business. Lincoln’s father, Mike, ran the family’s cotton compress and warehouse in the nearby town of Sudan, putting Lincoln and his younger brother, Garrett, to work hauling bales of cotton via forklift in the hot Texas sun.

The work was strenuous enough to teach Lincoln Riley the intended lessons about hard work and responsibility — but also to convince him he had no interest in inheriting the family business.

“My dad worked me enough there throughout the years that he broke me on that,” Riley joked during an interview with The Times last week.

But he happily embraced the family’s other enduring legacy in town, as the third of four Rileys to quarterback the Muleshoe Mules. His grandfather, Claude, was the first, leading the Mules to an undefeated season in 1938.

A newspaper article from the Clovis News Journal about USC coach Lincoln Riley during his high school days is on display at his parent’s home in Muleshoe, Texas. (Bryan Terry / The Oklahoman)

“That was the best the town had ever done,” Wood said, “until Lincoln.”

In West Texas, Muleshoe’s team was for decades a source of disappointment. Coaches came and went. Muleshoe football, as Riley remembers, was “one of the worst programs in the entire state of Texas for a long time.”

Mike Riley, Lincoln’s father, was a Mules quarterback through some of those down years. According to the Dallas Morning News, the Mules scored just one touchdown during the entire 1969 season. But the worst of times came decades later, just as his oldest son was learning to love football.

“As soon as the band quit marching, it’d just be a few of us, some parents and the coaches’ wives in the stands,” Stacy Conner, pastor at the First Baptist Church and a Riley family friend, jokes.

Still, Lincoln Riley grew up loving the Mules — and football, in general.

“There were multiple years in which we were 0-10 or 1-9,” Atwood says. “We still attended all the games. We were huge Muleshoe fans.”

It wasn’t until Wood came to town in the spring of 1996 that the team’s fortunes started to turn around. The new coach inherited around two dozen players, barely enough to field a full team, and the program was plagued by a lack of discipline. The day he interviewed, Wood recalls, there were three fights in the school’s halls.

“He wasn’t afraid to change things up, to do things different from what had been done there. What had been done was history or tradition or how they’d always done it, but it wasn’t working. … I’ve always carried that with me.” — USC COACH LINCOLN RILEY ON WHAT HE LEARNED FROM HIGH SCHOOL COACH DAVID WOOD

There was backlash to his new, strict approach at first, too. But Muleshoe “wanted discipline,” he said. “The town wanted to be good. They just didn’t know how to do it.”

Years later, when asked what he’d learned from Wood, Riley wouldn’t hesitate to draw parallels to the situation he now steps into at USC.

“He brought a program and a culture to Muleshoe that hadn’t been there,” Riley said. “He brought belief and hope. He wasn’t afraid to change things up, to do things different from what had been done there. What had been done was history or tradition or how they’d always done it, but it wasn’t working. … I’ve always carried that with me. I’ve never been afraid to go against the grain if I felt like it was the best thing for the team, for the program. I certainly won’t be afraid to do it here.”

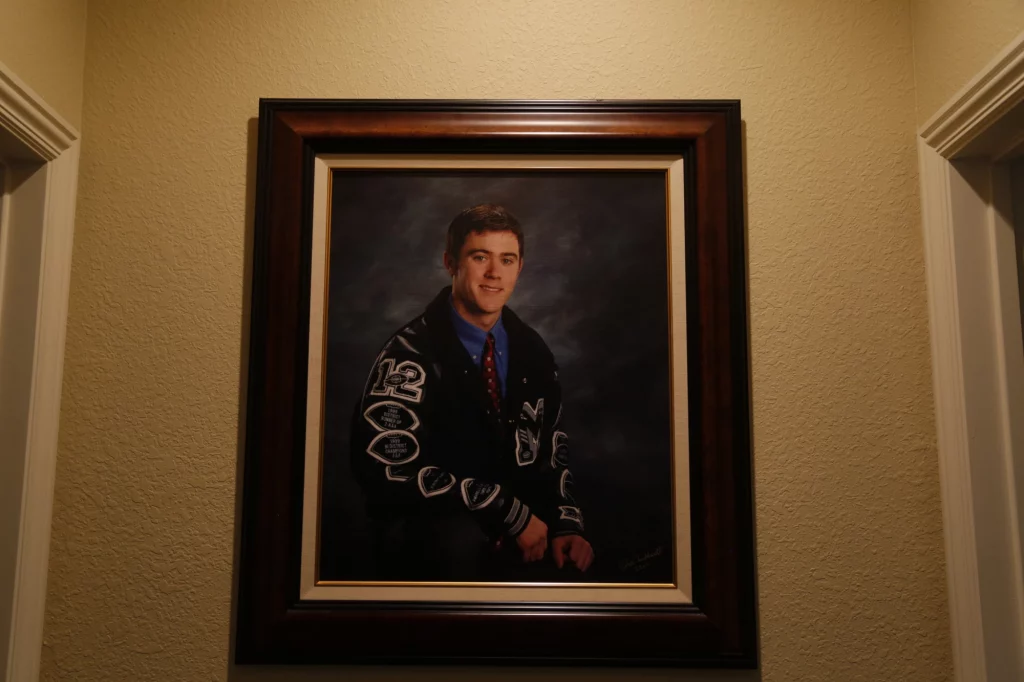

USC coach Lincoln Riley remains a celebrated figure in the Muleshoe High football program.

The Mules won one game in Wood’s first season, then five the next, giving Muleshoe its first non-losing season in two decades. When Riley was a freshman, the Mules won 10, including a playoff game. Momentum was building, and at quarterback, the attention turned to Riley, who Wood says was set to take the reins as a sophomore. But he dislocated his throwing shoulder before the start of the season trying to make a tackle during a practice. He played out the year on the defensive line instead.

Some speculate the injury might’ve changed his trajectory, but the next season, Riley led Muleshoe to new heights as its quarterback anyway. The town would never forget.

Over time, some of the Riley stories from those days have come to drift into tall tales, depending on who’s telling them. But everyone agrees that the boy was uncommonly bright, even if he didn’t take notes in class and sometimes skipped his homework. As a quarterback, Wood says, his intellect was his greatest asset. Later, when his younger brother, Garrett, quarterbacked the team, Wood consulted with Lincoln about their offense.

“He could think on the field unlike anybody else,” Wood said. “Lincoln has a photographic memory, and when I say that, I really mean it.”

At the helm of an I-formation, pro-style attack that bears no resemblance to the offense he ran at Oklahoma and will bring to USC, Riley led the Mules to an undefeated regular season in 2000. Muleshoe rolled through four playoff games on their way to the Class 3A state semifinals, including a rare win over Friona that inspired Riley and three teammates the next summer to climb the rival town’s water tower — and spray paint the winning score, 23-13, for all to see.

Atwood, who was one of the four, recalls that the boys were caught as soon as they descended the water tower. Today, he contends that their prank, now a part of town lore, was delayed payback for Friona painting the previous season’s score all over Muleshoe’s own weight room.

Two decades later, folks in town are still happy to relive that run through the state playoffs. Every Friday night that season, Muleshoe shut down. Caravans of pick-ups and SUVs would filter out of town for road games, packing visiting bleachers across the plains. Ellis, the mayor, says it “felt just like the movies.” For a small West Texas town obsessed with football, it was unforgettable.

“No one thought it was possible,” Riley remembers.

Muleshoe ultimately fell short in the state semifinals, losing handily to Forney High, a much larger school, 41-17. But by then, the town had already galvanized around its team, and Muleshoe was firmly on the football map.

“He could think on the field unlike anybody else. Lincoln has a photographic memory, and when I say that, I really mean it.” DAVID WOOD, LINCOLN RILEY’S FOOTBALL COACH AT MULESHOE HIGH

The run still resonates here. Wes Wood, the coach’s son who led the Mules to a state title as quarterback in 2008, said that season cemented Riley as his childhood hero. Few will ever forget Riley leading the Mules at Texas Stadium.

“Here’s little po-dunk Muleshoe playing in the [Dallas] Cowboys’ stadium,” said Wood, who’s now retired. “Back then, that was unbelievable.”

Eight years later, on the brink of that state championship, Riley returned to Muleshoe High for a pep rally. He’d recently been elevated to receivers coach at Texas Tech after years spent endearing himself to then-coach Mike Leach as a student and grad assistant. His coaching career would soon take off into the stratosphere, leading him to East Carolina, then Oklahoma and now USC, but Riley was already a star in Muleshoe.

The whole town packed into the high school gym that day, glowing as Riley spoke. He told the team not to waste one second of its big moment. There was a reason they’d come this far. “Just do what got you here,” Riley said. “Don’t change anything.”

The crowd roared. Some folks waited afterward to get his autograph.

“He inspired the whole town,” Wood said. “That was pretty exciting.”

In a back corner booth at Leal’s, where cowboy hats line the front walkway and tables are filling ahead of the lunch rush, Bob Graves is still sorting out his emotions over fresh-baked tortilla chips. No one in Muleshoe was more thrilled with Riley as Oklahoma’s coach than Graves, who served as the voice of Muleshoe football broadcasts and has been a Sooner fan since 1947. His exit left him stunned — and, he admits, a bit disappointed.

“It was so sudden,” Graves says. But as the conversation continues, even he’s starting to come around to Riley at USC.

Lincoln Riley is introduced as the Trojans’ new head football coach at the Coliseum on Nov. 29, in front of a bustling city backdrop vastly different than where he grew up. Brian van der Brug / LAT)

There’s no shortage of small-town sleuths here still wondering aloud why Riley up and left the Sooners seemingly overnight. Some were convinced he’d leave for Louisiana State. Others speculate he wanted nothing to do with the Southeastern Conference.

“From what I understand,” Graves says, “he wants to build his own program.”

The theories are numerous, but some here who know the Rileys wonder if the sprawl of Los Angeles might offer a semblance of anonymity. That’s something they never felt in Norman, where fans would recognize Riley’s wife, Caitlin, at the grocery store and knew their daughters’ names.

“I just knew there were things I wanted to try to do. Life is too short, so don’t be afraid to go for it.”

USC COACH LINCOLN RILEY ON LEAVING HIS SMALL HOMETOWN OF MULESHOE, TEXAS

Garrett Riley, Lincoln’s brother, said he “had a little bit of an instinct that something like that may happen.” But even he learned his brother took the USC job via social media.

“He keeps things pretty close to his sleeve,” Garrett says.

Lincoln Riley isn’t surprised by the town’s confusion. Just like he isn’t shocked by the anger in Oklahoma. Even a few weeks ago, he says, “if you would’ve told me I was living in L.A., I don’t know that I would’ve believed you.”

He looks back fondly on his upbringing in West Texas and the lessons it taught him. “It shaped who I am,” Riley says. But growing up, he always knew that he would leave.

“I just knew there were things I wanted to try to do,” he says. “Life is too short, so don’t be afraid to go for it.”

New USC football coach Lincoln Riley grew up in Muleshoe, Texas. (Ryan Kartje / LAT)

That notion crossed his mind the last Sunday morning in November, as he decided within a few hours to leave the comfort of Oklahoma for the uncertainty of USC. The idea of moving to Southern California was, he admits, pretty daunting. “There was some nervous energy,” Riley says. But as he and his wife considered the idea, Riley thought of his daughters.

“Conventional wisdom would say that you guys have been smallish-town people. That’s what you grew up in, that’s what your daughters are used to,” Riley says. “Conventional wisdom might tell you to stay in that, that’s what you do, and I certainly think that would’ve turned out just fine. But I think we saw this move as potentially a chance for them to experience new things, and when they get out in the real world — which will come way too quick — I want them to have been exposed to different things and different areas and different kinds of people. That part has always been important to me.”

The two weeks since that decision have been a whirlwind in both Los Angeles and Muleshoe, even if the definition differs in both places. At USC, expectations are already soaring. Fans are already convinced Riley’s arrival signifies a triumphant return to the Trojans’ rightful place atop college football.

In Muleshoe, no one needs any convincing. Sure, maybe they wouldn’t have chosen California as their favorite son’s next step. But like L.A., they have complete faith now that Lincoln Riley will deliver. He always has.

“It won’t be long,” Wood assures. “He’s gonna make the Trojans a powerhouse again.”

latimes.com

_________